Over the past few years, child care and early education have emerged as key public policy problems. This trend has come about in a time of increased participation in the workforce by mothers and rising costs for childcare.

With the growth of childcare as a public policy problem, child care subsidies have become a larger part of US antipoverty policy. In particular, child care subsidies help families fight poverty in two ways: by providing parents with resources and by giving children a boost that leads to wage growth down the road.

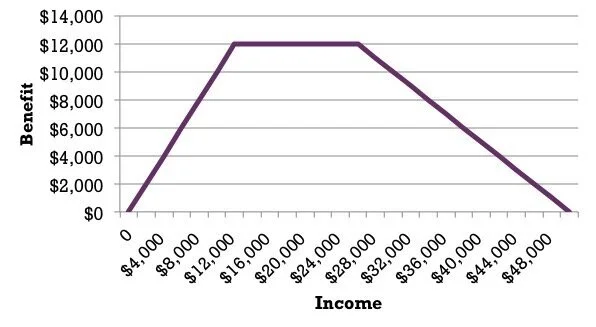

Child care subsidies reduce current poverty

A child care or preschool slot provided for free to a family has the effective value of $9,500 in Ohio. This makes the total benefit for a family with two children ($19,000) higher than the average social security benefit ($17,000 annualized), the average unemployment benefit ($16,000 annualized), the average disability benefit ($9,000), the average Medicare benefit ($8,000), the average Affordable Care Act tax credit benefit ($6,000), the average Medicaid benefit ($6,000), the average Pell Grant ($4,000), the average earned income tax credit ($3,000), and the average SNAP (formerly “food stamps”) benefit ($3,000 annualized).

Data sources linked above

While one child in public childcare eclipses seven of nine major safety net items above for the average recipient, two children in public childcare makes public childcare the most generous major safety net measure in the United States, worth 91% of the value of the federal poverty level for a family of three, even though public benefits such as child care benefits are not counted in measuring income towards the official poverty measure. Child care subsidies are an important tool for reducing poverty among poor families directly.

Child care subsidies alleviate intergenerational poverty

In addition to supporting families today, child care subsidies can be a tool for fighting intergenerational poverty. High-quality early childhood education has been shown in experimental settings to have wage benefits down the road for low-income children in particular in addition to crime and health benefits. In Timothy Bartik’s book Investing in Kids, the labor economist models a universal pre-k program with income-based fees, coming to the conclusion that the long-term wage boost to low-income children would be 11,000 times as large as the wage boost to high-income children as a function of previous expected wages.

If child care subsidies are progressive and ensure proper quality, they can be an effective tool for breaking intergenerational poverty.

Poorly deployed childcare subsidies can hurt families and children

While these results seem to paint a rosy picture for child care as a tool for equity, results from Canada should give us some pause. In the late 1990s, Montreal instituted a universal child care program without any quality controls. An analysis comparing Montreal to other provinces after the reform found children to have higher anxiety and aggression and worse development scores and health outcomes after the reform, while parents exhibited more hostile, inconsistent parenting behaviors along with less parental satisfaction and even higher levels of maternal depression. One of the possible explanation for these results is that children were getting less time to interact and build strong relationships with parents at young ages.

The balance of the evidence suggests that childcare subsidies smartly deployed can be a strong tool for reducing family and intergenerational poverty. That being said, subsidies should be deployed with caution in order to ensure that they are targeted towards high-quality programs and that they do more to encourage rather than discourage positive family interactions.