If you’ve been to a public meeting about poverty, you’ve probably seen someone stand up and smugly let you know about a little thing called a “benefits cliff.”

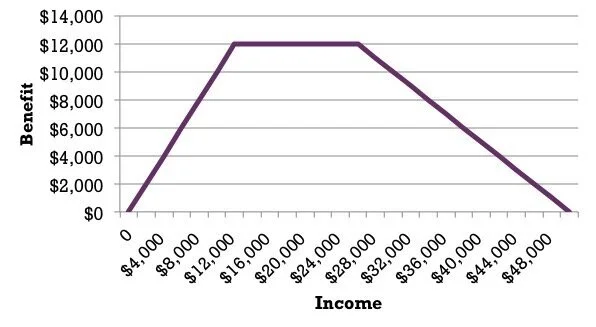

If you haven’t heard of a benefits cliff, here’s a simple explanation: a well-designed social welfare program has a “phase out” schedule. The idea is that if you make more money, you slowly lose your benefit. Take the earned income tax credit. The earned income tax credit slowly phases out for people making more income so that beneficiaries of the credit don’t lose all their money at once.

Figure 1. EITC Model

Compare this to a program like SNAP (formerly “food stamps”), which has a strict income cutoff, after which you are no longer eligible for the program. So in Ohio, if a single worker makes $16,000 in a year, she is usually eligible for about $2,400 in food assistance, making her effective income $18,400. But if she crosses that wage threshold and make $16,500, she loses her benefit, meaning her effective income drops by almost $2,000—just for getting a raise!

Figure 2. SNAP Model

Emily Campbell of the Center for Community Solutions is Ohio’s resident expert on benefit cliffs. She had modeled benefits cliffs for different family sizes and has presented extensively on the topic. As you can see from the graphic below, benefit reductions should theoretically slow income growth at many points in the income distribution.

Figure 3. Center for Community Solutions Benefits Cliff Model

In particular, according to this model, we should see a lot of single-parent two-child families “clumping” at about $17/hr annualized, which equals about $35,000. This is because, according to this model, making anywhere from $35,000 to $56,000 annually results in the same net income, so less work is better in this situation.

When I studied this problem as my capstone in graduate school, I found some evidence of clumping in publicly-available income data, but the effects were small. While there is a lot of theory and anecdotal evidence of the impact of benefits cliffs on work output and human capital development, there is little empirical evidence to demonstrate these impacts are actually happening.

Reasons to be skeptical about arguments about the impact of the benefits cliff include behavioral explanations. Human beings are pretty lousy at interpreting the tax and benefit system. It’s hard to make the argument on one hand that low-income people need financial literacy training and on the other hand that they are deciphering a complex benefits system to maximize their return for a given work input.

That being said, it is hard to argue the benefits cliffs have no impact at all. In my capstone work, I did detect some evidence for limited “clumping” at certain incomes which could have been driven by benefits cliffs incentives. So what do we do about these design problems?

The first step is to acknowledge them for what they are: design problems. It is pretty easy to redesign programs to phase out benefits rather than reducing them all at once: it’s just a change in the benefits schedule. The state of Ohio did it recently with child care benefits, albeit in a convoluted way by only allowing the phase-out range to apply to previous recipients (take your kid out of child care for a month and get a raise? Lose your benefit) and thus building in a strange incentive for benefit continuity. That being said, the new program creates less negative incentives than the last. Smart design can prevent these problems from occurring in the first place.

States are more hamstrung with federal programs like SNAP which have strict income cutoffs which states generally don’t have the flexibility to change. This is where states need to get creative. Case management combined with targeted cash or in-kind transfers can help supplement income when benefits disappear, creating bridges towards sustainable middle-class incomes. But the best way to deal with a benefits cliff is to make sure it doesn’t exist in the first place, which means good design at the onset of a program.

Rob Moore is the principal for Scioto Analysis.