Just over two weeks ago, the Trump Administration declared a “crime emergency” in Washington, D.C. in response to a former DOGE staffer getting injured in an attempted carjacking. As rationale for the emergency, the Trump Administration has described crime in D.C. as “out of control” and has named the District itself as, “by some measures, among the top 20 percent most dangerous cities in the world.” In January of this year, the Metropolitan Police Department announced that crime in D.C. reached the lowest it had been in 30 years.

The Trump Administration has since taken control of the Metropolitan Police Department and deployed the District of Columbia’s National Guard in an effort to reduce crime in the city. Earlier this week, President Trump signed an additional executive order with guidance to staff the National Park Service with more police officers, hire additional attorneys to prosecute violent crime, and increase law enforcement training and resources, all to help crack down on crime in the District of Columbia.

The 1973 Home Rule Act gives the president the ability to invoke this kind of power by granting presidential control over the national guard in the District of Columbia and allowing presidential use of the local police during emergencies. These emergencies are permitted to last for up to 30 days without legislative authorization.

The Home Rule Act has been invoked by presidents in the past, but never for reasons as broad and sweeping as crime. Prior to the current deployment in the District of Columbia, the most recent instance a president bypassed a governor to deploy state troops was to protect civil rights advocates in the 1960s. The use of the Home Rule Act and the deployment of the National Guard to fight everyday is unprecedented and is sure to face legal challenges and political pressure.

Research from Brown University finds that in the past, military policing has done very little to actually reduce crime. The study focuses on Bogotá, Colombia, one of the cities President Trump has compared crime rates in the District of Columbia to. The study finds that military forces seldom decrease crime more than traditional police forces, and in many cases, crime rates end up higher than before once military forces leave.

This data corroborates the concerns lawmakers in the District of Columbia have voiced. The National Guard does not receive the same type of training that local police officers receive on when and when not to use lethal force. Typically, the National Guard is used for more specific use cases, such as engaging in crowd control for protests, helping in the aftermath of a natural disaster, or controlling civil unrest. And, when it comes to handling crime, the National Guard acts more in-line with the military strategy of neutralizing dangerous threats than the police strategy of solving crime. In conjunction with recent reports of the National Guard carrying firearms, safety concerns in the District of Columbia are not without reason.

This poses the question: is deploying the National Guard an efficient use of resources to stop crime?

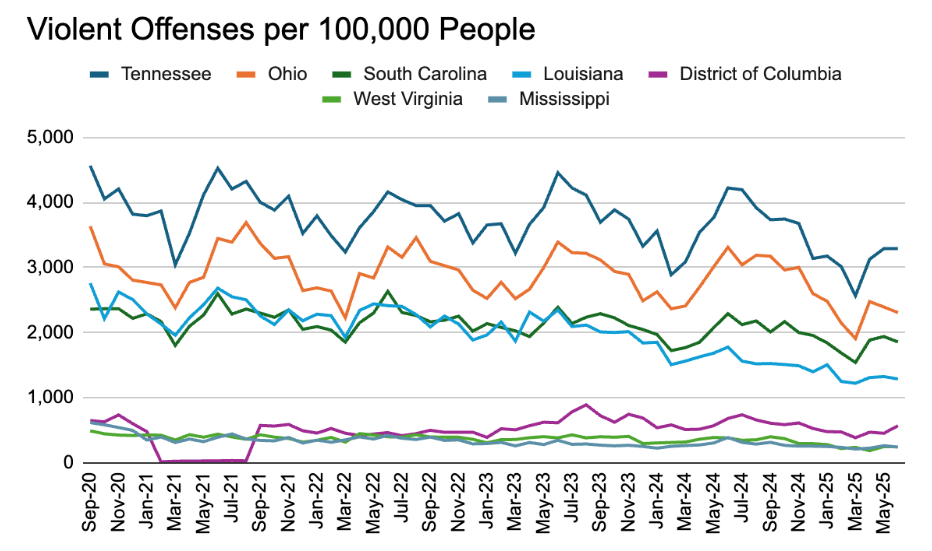

As of August 20th, six states have promised to send their National Guard troops to the District of Columbia: Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio, South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia. These troops will add more than 1,100 new soldiers to patrol the streets in the District of Columbia.

Using FBI crime data, violent crime rates from these states compared to Washington, D.C. are shown in the chart below.

Out of the six states that have promised to deploy the National Guard to the District of Columbia, the rate of violent crime per capita in Washington, D.C. is only higher than two, West Virginia and Mississippi, both of which have fewer urban areas than the other states. Even if deploying the National Guard is an effective way to reduce crime, why aren’t states with crime rates higher than the District of Columbia deploying the National Guard in their own cities? In this case, it seems subnational policymakers have deferred local interests to federal interests.

Once troops are sent from the states, Washington, D.C. will have upwards of 2,100 troops deployed. More than half of these troops will be from states, and the total cost of these troops could exceed $1,000,000 per day, meaning that states could be collectively paying upwards of $500,000 per day to keep troops in the District of Columbia. At Scioto Analysis, we focus on state and local policymaking, and the question persists– is deploying troops to the District of Columbia a good use of state resources?

So far, the Trump administration has cited robberies down 46%, carjacking down 83%, and violent crime down 22% in the District of Columbia due to the executive orders. While the source of this data remains unknown, if these figures are accurate, it remains unclear if crime will continue to fall once the National Guard leaves, or if it will rise to levels at or higher than before the National Guard was involved, as historical precedence suggests it may.

Historically, effective strategies to reduce crime in the long-run focus on institutional change and local based efforts such as vocational training, extra police patrol, rehabilitation programs, incarceration for repeat offenders, and quality education for high-risk youth, while ineffective strategies include community mobilization against crime, high supervision based programs, and arrests for minor offenses. Policymakers may have more work to do if they wish to make further progress on crime in major U.S. cities.