The state of the American education system can be pretty discouraging. Despite the challenges levied inequities in achievement, uneven funding, and disparities in graduation rates, though, many policymakers are still striving to increase the number of students in poverty experiencing academic success. But where should they start?

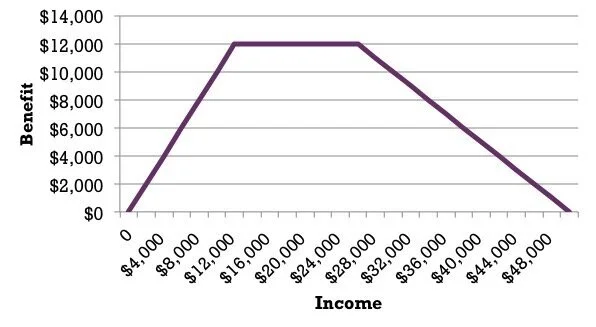

One place to look is the Washington State Institute for Public Policy’s Benefit-Cost Database. We’ve used WSIPP to look at workforce development strategies before, but the state cost-benefit analysis database also has information on interventions that range from criminal justice to health care to higher education. Here, we look at pre-K through 12 interventions.

These results need to be taken with a grain of salt. While the methods are rigorous, they are prepared for policymakers in Washington State, so the policy may operate differently in a place like Ohio. That being said, they still give us some guidance for policies that be used to improve academic outcomes for students in poverty. Below are the three programs that have the highest per-participant net benefits in WSIPP’s education policy database.

Becoming a Man (BAM) with High-Dosage Tutoring

“Becoming a Man” is a cognitive behavioral therapy-based behavioral program focused on skill training and exposure to prosocial adults for disadvantaged high school-aged young men. This program is conducted in a one-hour weekly group sessions where participants learn character and social-emotional skills such as considering others’ perspectives, evaluating consequences ahead of time, and reducing automatic decision making. WSIPP’s analysis evaluated the impacts of Becoming a Man combined with daily, two-to-one ratio hourly math tutoring sessions.

While the program costs $4,700 per participant, it yields over $40,000 in per-participant benefits due to improved test scores and increased labor market earnings associated with them. This means that not only does the program yield net social benefits, but the increased wages garnered from the program will lead to increased tax revenue that will pay for the cost of the program in the long run. This also means that a federal (or even a state) government would be incentivized to fund such a program for budgetary reasons alone.

The drawbacks of Becoming a Man are typical. Like any educational intervention, the payoff takes time. WSIPP estimates that about 12 years will pass before the benefits of this program exceed the costs. This is faster than some other educational programs since its participants are high-school age, but still some time to wait. Additionally, the program has some uncertainty to it. Since this program has only been evaluated in limited circumstances and benefits hinge on the program leading to test scores which lead to labor market earnings, there is some uncertainty about whether they will pan out. In the limited evaluation of the program that has been carried out, though, the results were so positive that WSIPP is optimistic about future applications of this model.

Consultant Teachers: Literacy Collaborative

While Becoming a Man focuses directly on students, the Literacy Collaborate model indirectly impacts students by coaching teachers. Literacy coaches are trained for up to 35 days at local universities then provided with ongoing training support after placement in schools. Coaches work one-on-one with teachers to improve instructional practices. The evaluation WSIPP used focused in particular on the impact of the model on classrooms with children in early primary years, grades K-2.

Literacy Collaborative costs are very low, coming out to only $780 per student according to an Ohio State University study of the program in Columbus, Ohio cited by WSIPP. This means the program costs one-sixth the cost to operate as Becoming a Man. This is likely because of the “teach the teacher” model, where less resources can be used to impact more students. Benefits are also large, at about $28,000 in new future labor market earnings per child impacted, less than Becoming a Man but still substantial. This means it is also a program that “pays for itself” down the road.

This program has one similarity to Becoming a Man and one glaring difference. The similarity is that the program takes a long time to pay off, though even longer than Becoming a Man at an estimated 16 years before the program yields net benefits. The difference is that the WSIPP Monte Carlo simulations used to predict the probability the program has net benefits showed net benefits in 100% of simulations. This means that the program is a slam-dunk to provide benefits if carried out correctly in the right environment. This is likely because of the program’s low cost: as long as it can cover the $780 per student, it will yield net benefits.

Double-Dose Classes

The final of these three programs is deceptively simple: double-dose classes. If a student is struggling in math or reading, that student will be enrolled in two math or reading classes instead of one, thus doubling their instructional time.

It is surprising how effective this simple intervention is. At the low cost of only about $500 per participant (marginal costs of another student in another class are fairly low), about $18,000 in new future labor market earning benefits are accrued. In addition, there is a small impact on crime from the program as it has been found to reduce crime rates as well. Because of its low cost and the future labor market benefits, the program also pays for itself in the long run.

Double-dose classes have certainty of yielding net benefits of near the same level as Literacy Collaborate, with 98% of simulated scenarios resulting in a net-benefit program. Additionally, double-dose classes yield benefits in about ten years, quicker than Becoming a Man or Literacy Collaborative.

These are only three of the 42 educational programs WSIPP has determined yield net benefits, so it really only scratches the surface of tools policymakers have to improve academic outcomes for students in poverty. What I take away from this, though, is that there is no reason to get cynical about K-12 education in the United States. We have tools that work: we just need to use them.