Last week, the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services announced $13 million in new grants awarded to community organizations trying to reduce opioid overdoses in the state. That’s right, another epidemic is still raging while we tap the “refresh” buttons on our browsers hoping for our COVID-19 vaccination appointments.

According to the most recent data from the CDC, about 5,000 Ohioans died from drug overdoses from September 2019 to August 2020. This is nearly 14,000 less than died from COVID-19 in the state so far, but would still put drug overdoses in the top ten causes of death in Ohio in 2017, the year we have the most recent data for.

Also concerning is that drug overdoses are up in Ohio. While the state is still a few hundred annualized deaths below the drug overdose peak in 2016 and 2017, recent overdoes are up from the recent trough of 4,000 annualized deaths in 2018.

The CDC has sounded the alarm on the increase in overdose deaths that has coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. Whether this is a result of economic uncertainty, widespread social isolation, or a sort of co-occurrence with other health phenomena is yet to be determined, but deaths are certainly up.

Social distancing provides new challenges for people seeking treatment as well. The best practice for treatment of opioid abuse is medication assisted treatment. But due to the addictive nature of medications used to wean people off painkiller and street drug addiction, effective medications like methadone and buprenorphine can only be disbursed daily or weekly. This means people needing treatment must go for in-person meetings every day or once a week in order to get the treatment they need.

The problem with a treatment like this should be obvious even outside of a global pandemic marked by social distancing. But it is made even harder under the circumstances of the past year.

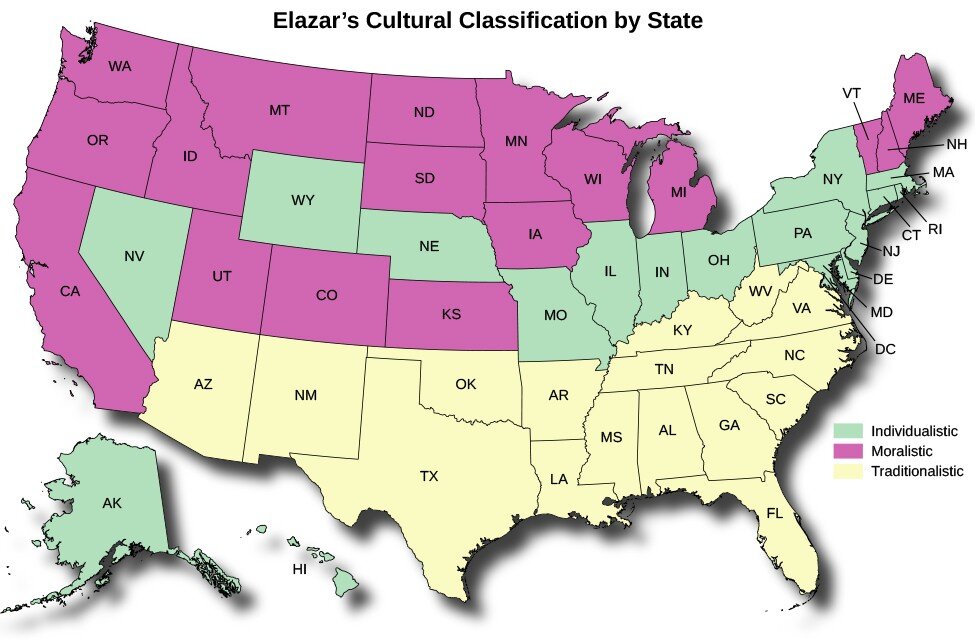

So what solutions are there to this problem? Well, this is a tough question to answer. Medication assisted treatment is the best tool we have for treating opioid addiction and preventing overdoses. Some states, like Vermont, have created effective statewide treatment systems that connect patients with the kind of treatment they need and make the geography meet the patient where her need is, not the other way around.

Ultimately, though, we want to get to the point where we are preventing opioid addiction rather than just treating it after the fact. The limitation we face here is that we still don’t know what it is that is causing opioid addiction. Some of the most cutting-edge research on the opioid epidemic seemed to suggest that prescription prevalence was the biggest driver of opioid deaths. In this case, prescription drug monitoring programs should have made a dent in opioid deaths.

And maybe they have. There is a distinct possibility that we haven’t risen above 2017 overdose death numbers because of prescription drug monitoring and other steps that have been taken to reduce the supply of addiction painkillers. But we’re still seeing persistent death numbers.

It will be interesting to see if the American Recovery Act has any impact on death rates. Maybe the old “deaths of despair” narrative has more to it than we realized. If so, injecting a bunch of money into households could hold back these deaths. Then again, we might have dug ourselves in so deep with this current epidemic that there will be little attention paid to the other one, despite the work community groups continue to do to reduce drug overdoses across this state.

This commentary first appeared in the Ohio Capital Journal.