Do different states have different “political cultures?”

That’s the argument that is made by Daniel Elazar, a 20th-Century University of Chicago political scientist who was a leading scholar of the politics of the US states. Elazar breaks US states into three different categories: moralistic, individualistic, and traditionalistic.

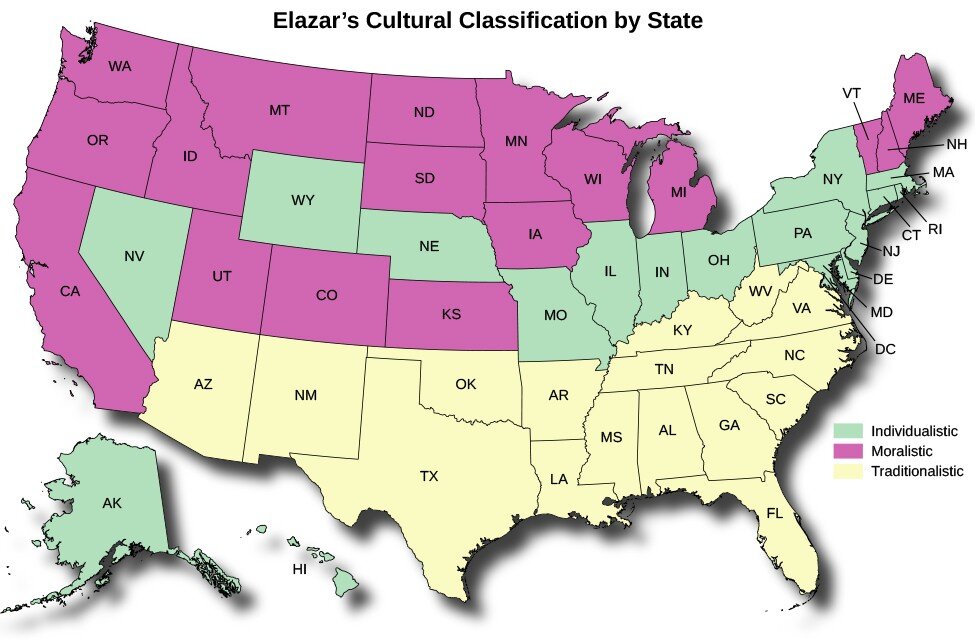

According to Elazar, moralistic states are states that were settled by puritans and northern Europeans. Moralistic political culture is defined by idealism, the idea that politics can be a vehicle for solving social ills and that we can use the democratic process to find solutions for public problems. Moralistic states are concentrated in New England, Upper Midwest, and West.

Individualistic states are more cosmopolitan and diverse. Politics in individualistic states are defined by barter and negotiation, with politics being defined as a space where various factions and interests split up the pie of public cooperation. While a moralistic political culture will bring people together to the same table in order to get an understanding of a problem, the role of testimony in an individualistic political culture is to see where interests stand and to make sure they all are balanced when policy is created. Much of the mid Atlantic and lower Midwest is described by Elazar as individualistic.

Lastly, there is traditionalistic political culture. Traditionalistic states are states that are run by elites. These states tend to be defined by one-party rule for decades on end and are run by people in the “aristocracy,” usually wealthy people who come from wealthy families. Elazar describes much of the South, Southwest, and Appalachia as “traditionalistic” in its political culture.

Things have changed since Elazar pioneered this typology in the 20th Century. We can argue, for example, that much of the West skews more individualistic these days. But I find it surprising how accurate this typology still seems to be. Republican governors in Vermont and New Hampshire sound a lot different from their counterparts in Southern states. There is certainly a story about partisanship here, but I think the fact that these governors have continued to win in these states against Democrats speaks to a certain moralistic pragmatism from voters.

I certainly saw this difference moving back to Ohio a few years ago from the west coast. Even local government in the Bay Area had a deep commitment to policy analysis and problem solving that seemed markedly different from the way politics is handled in Ohio. Even compared to Nebraska, which was classified as “individualistic” by Elazar, the politics in Ohio seemed nakedly transactional.

How does this impact public policy? Well, public policy is treated differently if it is seen as a problem solving exercise, a negotiating table, or a fiat of the deserved rulers. Moralistic political culture comports much more with public policy as it is taught in graduate schools, with problem definition and then construction of alternatives and analysis of these alternatives leading to policy prescriptions.

Individualistic and traditionalistic political culture can use policy analysis as well, though. How can we understand how to split the pie of public policy if we don’t know what that pie looks like? How can we have good discussions about who gets what if we don’t know what we have to divide? These are questions that are important in an individualistic political culture. In a traditionalistic political culture, rulers need to understand what they’re doing if they’re trying to advance their own interest. Policy analysis even has a place there.

Ultimately, it seems that moralistic political culture is best suited for policy analysis as we tend to define it. This could mean that policy analysts have a reason to advocate for political reforms that push politics in a more moralistic direction. It also could mean that policy analysts need to adapt to cultures that are more individualistic or traditionalistic. I’d wager that better public policy requires both modifications, deployed at different times, with a mind for the appetite that people have for change and the particular leaders in power at a particular time.