Last week, Robert Santos decided to step down as the director of Census Bureau. This decision comes at a time when the Trump administration is making a concerted effort to remove public data from government websites due to a perceived connection to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The Trump administration’s war on DEI practices has escalated. It is no longer about stopping workplace sensitivity trainings or changing hiring practices, it is instead focused on changing the way people in this country understand people that are different from them.

Things are changing quickly, and it’s difficult to predict what the extent of these data removals will be. For example, the Center for Disease Control’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (one of the best publicly available health databases) was temporarily taken down. As I’m writing this on Wednesday, February 5, parts of it are back online.

I imagine that most people who read blog posts on sciotoanalysis.com understand the importance of this kind of data, but the severity of this situation is worth repeating. Policymakers, non-profit organizations, academic researchers, and others rely on the availability of high-quality public data.

Fortunately, researchers have been working to download as much data as possible in the event things do start to get taken offline. We won’t completely lose the data that already exists, even if we might not be able to use new data going forward.

That being said, it is hard to imagine that over the next four years, the newly collected public data is going to be of the same quality. If I had to guess, I would say that we probably aren’t going to have nearly as precise data on things like gender, race, sexuality, etc.

It might be the case that those questions are removed entirely from government-run surveys like the American Community Survey. I am optimistic that those surveys won’t entirely disappear. Much of this optimism comes from the fact that I can’t even begin to imagine how damaging it would be to have the decennial census be the only piece of publicly collected national data.

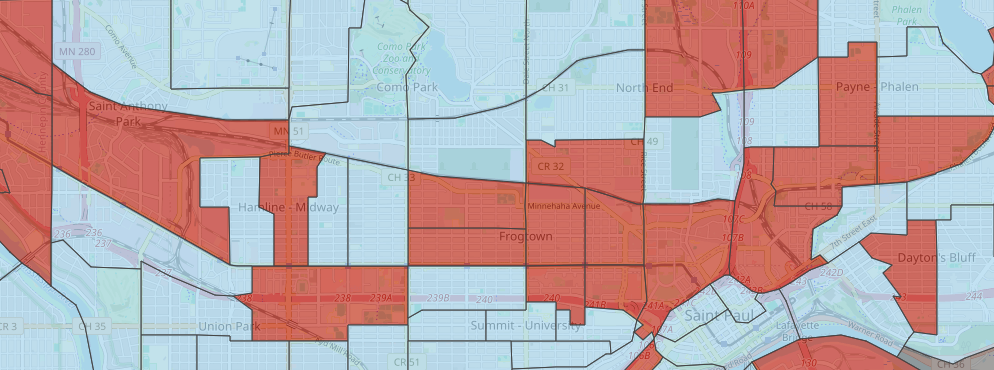

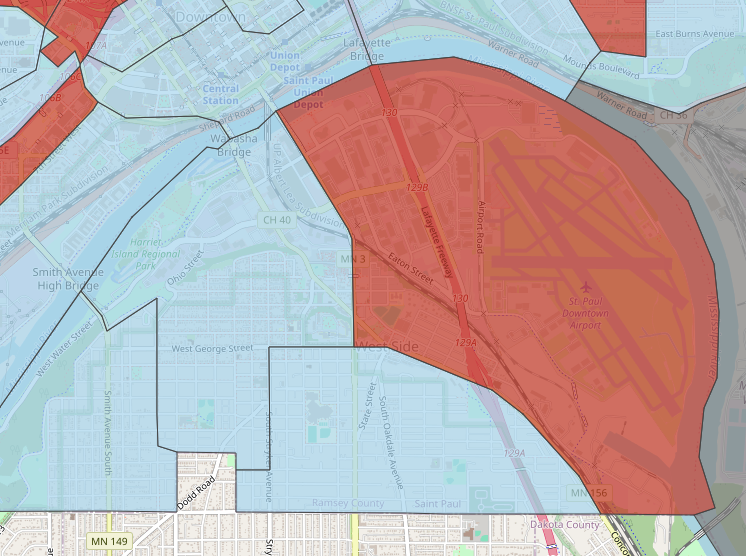

Still, a lot of harm will come from failing to collect adequate data. One example that comes to mind is thinking about how the Census Bureau records race data. Currently, there are only six race categories: White, Black, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander, and Other. This does not do a good job of capturing the different racial identities people in the United States have.

The Census Bureau decided in 2024 that it would add North African/Middle Eastern as a racial category, an important change that would have helped improve our understanding of racial dynamics. I don’t know if the current version of the American Community Survey is already in progress with this updated race question, but I would be very surprised if this data ever became public.

As a researcher, it’s hard not to be discouraged by the thought of losing so much data over the next four years. But I want to end on a slightly more optimistic note.

Yesterday, I was talking with a community group of data scientists. Near the end of our chat, this topic came up. While people were still extremely nervous about whether or not we would continue to have access to high quality data, the people in that meeting were still very optimistic. People were sharing the data repositories they knew about that wouldn’t be taken down and talking about how we might address these shortcomings going forward.

Right now, we don’t know to what extent we are going to lose data. As statisticians, it is our job to ensure that going forward, we don’t leave groups behind just because we are losing data about them. We likely won’t be able to rely on the Census Bureau as much in the short-term, but we can still explore effectiveness, efficiency, and most importantly right now, equity.