A few years ago, I first heard about a research project conducted by United Way affiliates called ALICE.

ALICE stands for Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, and Employed. The goal of the ALICE project is to estimate the number of people in every community who fit into this category. Why does this category matter? Because people with low levels of assets, limited income, and employment still often cannot afford what we call “necessities.”

How do we know if someone lives in an ALICE household? Well, it’s very similar to how we determine if someone is below the federal poverty level: researchers set a threshold based on some conception of what qualifies as sufficient income. If a household has income below that threshold, they are an ALICE household. If their income is above that threshold, they are not.

The way ALICE researchers set the threshold is by adding up the local cost of a range of goods. This list comprises housing, child care, food, transportation, health care, technology, taxes, and other miscellaneous goods. This differs from the methodology of the federal poverty threshold, which uses the cost of food times three as its threshold. It also departs from the supplementary poverty threshold methodology, more popular among poverty researchers, which uses average spending amounts to anchor its threshold.

According to the 2022 ALICE report, 54 million of the United States’s 129 million households fell below the ALICE threshold. This means more than three times as many households are ALICE households than there are households in poverty.

Some have claimed that the ALICE framework should be a replacement for the federal poverty level. This means that policymakers should shift their focus from the 12% of households struggling the most to the 42% of households who do not have income that meets the ALICE threshold.

Policymakers have been making this shift for decades now. At last month’s Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management Fall Research Conference, a number of sessions focused on the changing nature of the federal social safety net. One of the biggest takeaways I took from these sessions is (1) that the social safety net is larger now than it was a few decades ago, and (2) that the social safety net has shifted from supporting people at 0-50% of the federal poverty line to supporting people at 100-150% of the federal poverty line.

A big reason for this is welfare reform in the 1990s. In 1993, a household claiming Assistance for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, colloquially known as “welfare”) could bring their total income over the federal poverty level with wage income at 0% of the federal poverty level.

Let the implications of that sink in: before welfare reform, the United States had guaranteed income for households with children.

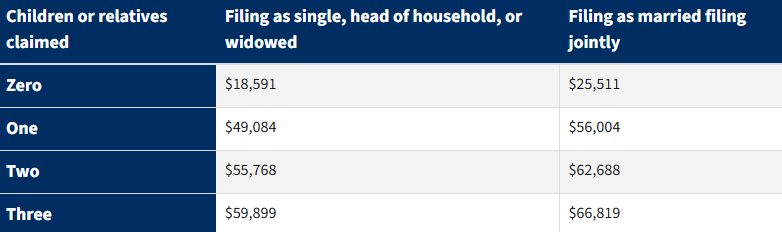

That changed with welfare reform. With Assistance for Families with Dependent Children transformed into Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the program was block granted and significantly reduced. What took its place was the Earned Income Tax Credit, a program that primarily gave cash to households with children with working parents.

The growth in the social safety net since then has been documented by Dr. Katherine Michelmore of the University of Michigan, who recently won the David N. Kershaw Award for this work. The growth in support for families has been on the backs of expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit in the decades since welfare reform.

This has led to a change in overall support for families. Overall, families are receiving more support today than they did in the early 90s. But this support has shifted from families at the lowest level of the income distribution to families who are at or a little bit above the federal poverty level.

This is because Assistance for Families with Dependent Children did not require a household to work to receive support. If a household had children, they needed support, so Assistance for Families with Dependent Children gave it to them. Today’s social safety net does not work that way. Both the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit require wage income to claim. This means our current social safety net currently supports low-income people who are near or above the federal poverty level, not people who are in deep poverty.

Despite the current structure of our social safety net, the fixation in safety net policy is still on people who are low-income but not below the federal poverty level. Policymakers’ attention to the “benefits cliff” is a great example of this. In Ohio, eligibility for food assistance was recently expanded significantly. Who was it expanded to? You guessed it–people at 130-200% of the federal poverty level. This likely means hundreds of millions of dollars of new annual support for low-income families, but none for families below the federal poverty level.

Helping low-income people should be no crime from a social welfare perspective. What worries me is who is left out of that conversation. ALICE purports to widen the scope of our safety net by demonstrating how 42% of families are struggling rather than only the 12% of families who are below the federal poverty level. But it sets its ALICE threshold for a family of four in Franklin County, Ohio with two parents, a preschool-age child, and an infant at over $91,000. The federal poverty level for that same family is about $28,000. Can we seriously say that a family of four making $90,000 should be lumped into the same category as a family of four making $27,000? Or that a policy that helps the family making $90,000 is just as socially beneficial as a policy that helps the family making $27,000?

This isn’t to say that ALICE is a bad framework: it helps us learn something, especially about the cost of goods that many families need to survive. But it also lumps a wide swath of the population together that are dealing with varying problems and can make us lose sight of those who are struggling most.

Great 20th Century Political Philosopher John Rawls put forth his famous “difference principle” in his 1971 classic A Theory of Justice. He argued that social and economic inequalities “are to be to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society.”

Helping people who are struggling is good. Supporting people who are dealing with problems like benefits cliffs is socially beneficial, but losing sight of people who are struggling the most is a huge problem in our current safety net. Our fixation on the population of low-income people above the federal poverty line has come at the expense of people in deep poverty. The longer we continue to follow this path, the more people who are the least-well-off will continue to suffer.