One thing I find interesting about income inequality is how, unlike other parts of our society that are widely believed to be a flaw, there is a strong economic case to be made that at least some inequality might be healthy. Severe income inequality is unacceptable, but it seems to be alright to allow people to earn different incomes based on different levels of contribution to society.

Compare this to something like pollution. We still tolerate some amounts of pollution as a byproduct of economic activity, but unlike income inequality, it would still be better if we could eliminate pollution entirely.

Income inequality is the byproduct of a wage economy where people earn more largely based on how difficult their skills are to replace. There isn’t a technological fix for this like there hopefully is for pollution.

To quantify income inequality, we most commonly look at an area’s Gini Coefficient, a single number that quantifies how far a community is from perfect income equality. A number close to zero means that a community has very low levels of inequality, and a number close to 100 means that a place has extreme disparities.

The World Bank calculates that the United States has a Gini Coefficient of 39.8, which is solidly in the top half of countries in terms of inequality. The highest national Gini Coefficient is South Africa’s 63, calculated in 2015. Of the more recently calculated numbers, Brazil has the highest at 52.9.

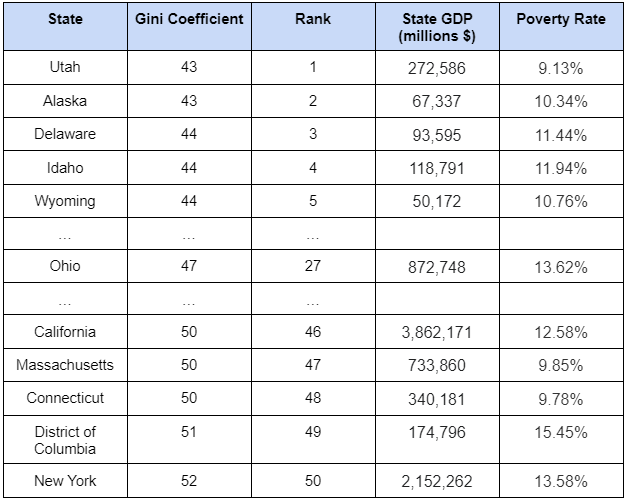

However, if we want to get a much more detailed picture of what income inequality looks like in this country, we can look at the Gini Index for each state. Below is the data as calculated and published by the Census Bureau.

A few things jump out to me about these results. First, all of these coefficients are higher than those calculated by the World Bank. An important thing to recognize about the Gini Coefficient is that it is sensitive to how it is calculated. In particular, the number of income bins used for each region.

Another finding is that it appears that a state’s Gini Coefficient is somewhat correlated with their total GDP. It makes some intuitive sense that states with larger nominal economies would have more inequality since we often assume that inequality is a tradeoff that comes with growth.

The states with low Gini Coefficients are relatively smaller, and have fairly low poverty rates. Alaska is a unique case because despite the fact that a large part of its economy is the result of its oil industry, it repurposes some of that profit to fund a basic income program as a state.

While the overall gap between states is fairly small (it is roughly equivalent to the gap between the United States and France on the World Bank’s list), it does highlight some important facts about state economies.

Right now, it appears that in the United States, strong economic growth results in high inequality, but that doesn’t have to be the case. Alaska is a great example of this, where by repurposing the benefits that arise as a result of their economic growth, they can prevent rampant inequality. Inequality is, at least partially, a policy choice.